By Tarteel Muammar1

The COVID-19 global crisis has sparked debate about the future of creative work and the effect of mobility restrictions and the prohibition of gatherings on exhibitions, live performances and all art manifestations that correspond to the presence of an audience in a common space. While public opinion seems generally unconcerned with this question and has not delved deeper into its consequences or addressed it specifically, it has been preoccupying many artists, individuals and institutions that work with the public. Opinions have varied between supporters and opponents of the idea of transferring and exhibiting works online, and of using the internet as a container for such productions. There was much doubt about the ability of this alternative space to create a useful exhibition experience and to trigger any meaningful interaction. In addition, many others expect the pandemic to remain for a long time, requiring art to exist through research and an openness to safe spaces and platforms.

Although most visual art spaces have presented their productions and collections with a focus mainly on archival materials, or have made exhibitions available through previously prepared channels, there is modesty in experiments that transcend technology as a tool, in contrast to it being a space that can be adapted and accessed, reaching a more interactive state between the works of art and technology and between technology and the audience.

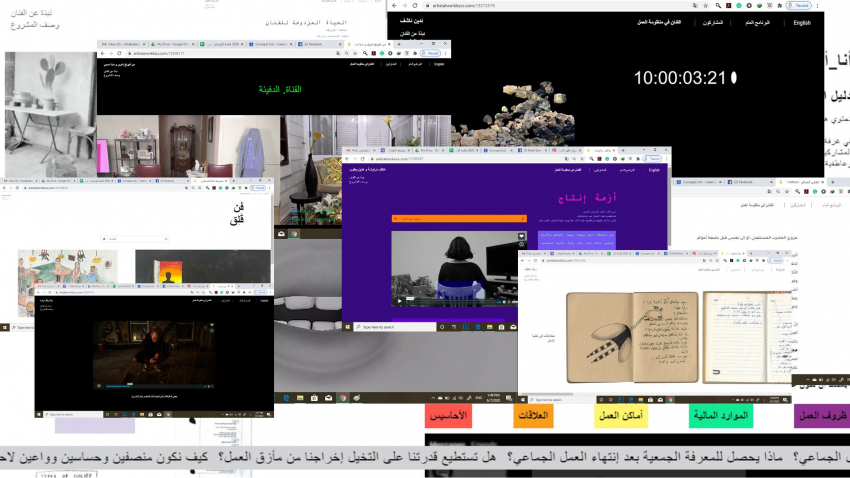

In one successful experiment, “Visual Arts: A Flourishing Field” (VAFF)’s partner, the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre (KSCC) in Ramallah, opened its first online exhibition on 4 June 2020, with an exhibition entitled “Artist at Work” curated by Noor Abed. The exhibition, featuring ten works by 16 artists from Palestine, Egypt, Lebanon, Korea and Brazil, offered a new local experience of virtual exhibitions, with four of the ten works by collectives and six by individual artists, of works that ranged in form from the visual and textual to sound. “Since the beginning of our confrontation with the consequences of COVID-19 on cultural work in Palestine, particularly the work of VAFF’s partners, we engaged in discussions, which are still ongoing today, to devise new ways of working that respond to the present circumstances, while also maintaining a flexible space that enables institutions to come up with new creative and distinctive initiatives including this exhibition” commented Yara Odeh, VAFF manager, about the exhibition. “From the outset, we assisted KSCC to transform their exhibition from the physical space to the virtual, to turn the challenges of these times into a successful and exceptional opportunity in a short space of time. With modest financial and technical resources, the exhibition resisted the enforced isolation, using technology to present the works and offering the artists a free space to express their ideas, experiences and fears in this new reality. All this took place virtually, reaching a wider and more diverse and engaged audience” she added.

The exhibition features a collection of works that explores the position of the artist within the current inherently unstable economic climate. It assumes, through the breakdown of the system, the nonexistence of an infrastructure that protects or looks after the art production sectors. Therefore, the system constitutes an economic structure in which individual artists in particular do not occupy a space. As the curator, Noor Abed, said: “In light of the recent global events, the ruptures and fragilities rooted in current economic models have been exposed, and so working on this exhibition under these circumstances became far more relevant.”

Whereas previously the space and the physical installation of the exhibition were essential in creating an “exhibition”, and online work was merely complementary, the situation has changed. In light of the current crisis, and the inability to gather in one space, the possibility of the audience’s presence and interaction with the space was not possible. This led the team at KSCC, with Noor Abed and in collaboration with the participating artists, to begin deliberating and discussing the feasibility of creating an exhibition under these conditions, and to consider how to adapt the internet to contain the exhibition in a manner that does not compromise its conceptual value and which suits its subject matter.

Each of the works was able to reflect its visual identity in the presentation by allowing artists to design the pages featuring their artworks according to their vision and with the help of the designer. Although this doubled the effort involved, it nonetheless produced a combination of visual and audio forms. At the same time, this transition provided an opportunity to reach a wider audience all over the world, which would not have happened if the exhibition had taken place physically at the Centre itself.

Renad Shqeirat, the director of KSCC commented: “As the new director, and in the transitional period, we began to think about the direction of the centre, of its management and of its social and cultural dimensions and their compatibility with our vision, and this is what we attempted to reflect in the exhibition. We tried to provide an open space for both the curator and the artists to develop and direct their works, based on their own vision. This created a complementary non-hierarchical partnership between us.”

Transferring the exhibition to the online sphere required substantial changes in the works of some of the artists. The initial open call was based on the presumption that the exhibition would open in KSCC’s spaces, but moving the project online meant, for example, transforming a proposal to turn KSCC’s garage into a temporary café operating as a non-consumerist model into a compilation of text messages received by the artist Felipe Steinberg. After the escalation of the crisis and the rise of new forms of communication, and with everyone under lockdown for weeks, Steinberg then developed a new work, “Not I, Not Here”.

Meanwhile, as a result of the disruption of everything around them, the crisis returned Akef Darawsheh and Hadeel Yaqoub to the exhibition’s first questions: “It is no longer only about a work structure that is confused, but also dysfunctional.” Through a video and an audio recording, their work entitled “Production Dilemma” tackles the restlessness of an artist in quarantine, as well as questions about production and its value in the midst of conditions of panic, fear and anticipation.

Other artists, such as the Hakaya Collective, adjusted the form of the presentation but not the content. They showed their work “Restless Art”, originally supposed to be a live performance using the hakawati style, via a pre-prepared audio recording.

This experience interrupted the usual rhythm of exhibitions. It caused a separation between the artist and the audience with the absence of any physical interaction, as well as leading to difficulties in communication between the artist and the curator. Yet it has, however, reset and reconfigured the means of communication and created a visual digital condition that allows us to enter a space that cannot otherwise be reached.

In addition to launching the exhibition online, a virtual public programme was developed based on the programme previously planned for the opening at the Centre. This included a series of lectures, dialogues and workshops that began before the opening of the exhibition, with the aim of developing some projects through it and this is still ongoing.

As part of the public programme, small production grants were also introduced to support the production of artworks, research, writings, critical material or lectures based on and inspired by the works featured in the exhibition. This aims to enhance the participation and engagement of the audience, and as part of the programme’s drive to support artists and art production.

The “Artist At Work” exhibition was able to break many moulds through innovating new options and redirecting us to reconsider ways of working when there is a lack of balance, safety, freedom and a sudden state of anxiety.

As the curator Noor Abed added: “From a personal perspective, this process provoked a state of reconciliation with the present moment, and with the idea of working blindly but freely with the uncertain or/and the unknown, or with what I no longer know.”

1Assistant Coordinator, “Visual Arts: A Flourishing Field” (VAFF) Project